Thresholds in Error Correction Codes

I’ve been reading about quantum computers recently. If so many organizations are beginning to migrate to post-quantum cryptography, it must mean the quantum threat is starting to take shape. As an outsider to the field, I can’t always tell where the line lies between fact and marketing fluff. Whatever makes the loudest splash in popular science articles tends to seem the most important.

One group that excels at generating fanfare is Google Quantum AI. Their “breakthroughs” arrive not only with research papers but also slick videos featuring senior management—and occasionally, a small bump in Alphabet’s stock price.

The Breakthrough Paper

One such milestone from Google Quantum AI last year was their paper, Quantum error correction below the surface code threshold. I saw the news coverage and watched the videos, but didn’t really understand what made it significant. Since I wanted to learn more about quantum computing, I decided to dig deeper into this particular result.

The first paragraph of the paper actually explains the context quite clearly. It states:

\[\epsilon_d \propto \frac{p}{p_{thr}}^{(d+1)/2}\]If the physical operations are below a critical noise threshold, the logical error should be suppressed exponentially as we increase the number of physical qubits per logical qubit. This behavior is expressed in the approximate relation

In other words, Google’s qubits have now reached a low enough physical error rate for quantum error correction (QEC) to actually work as intended. No one had previously demonstrated this exponential suppression of logical errors, because earlier physical qubits were simply too noisy for QEC to take effect.

Drawing Parallels with Classical Error Correction

As I read more about quantum error correction, I came across the Threshold Theorem. Interestingly, the theorem discusses only quantum error correction. But I felt that classical error correction must have an analogous idea too.

In classical communication systems, applying error-correction codes makes the bit-error-rate vs SNR curve steeper. Above a certain SNR, error correction exponentially reduces the logical error rate. But below that point, the code can actually make performance worse. That sounds a lot like a threshold.

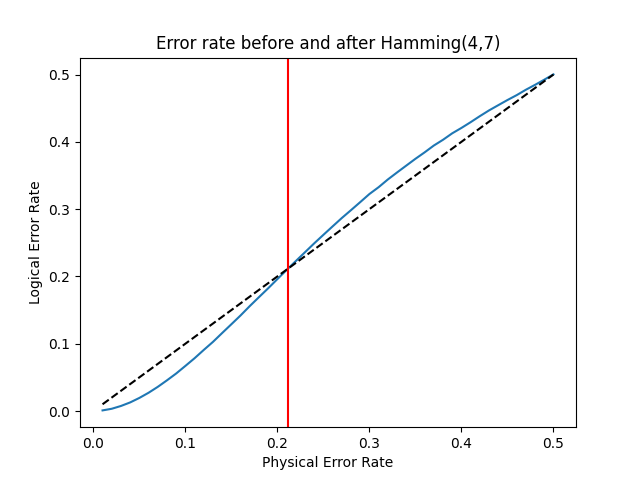

To test this intuition, I ran a quick C++ simulation using a simple Hamming(7,4) code.

Sure enough, a threshold appears around a physical error rate of 0.211. Above that, the Hamming code degrades performance rather than improving it. I wonder if this threshold value can be derived from first principles.

Reflection on Cross-Domain Training

In communications and signal processing, we rarely talk explicitly about “thresholds” for error-correction codes. At best, we say a code can correct up to x number of bit flips. But the threshold concept still exists—just not described in those terms. As I often say, innovation happens at the intersection of domains. In this case, a curiosity-led study into quantum computing returned with a refreshing new view on a mature topic.