Orthogonal Time Frequency Space

Digital modulations schemes have been invented and studied since a long time ago. Frequency Shift Keying (FSK) was one of the earliest digital modulation invented. Its origins are tied to RTTY systems which alternates between two frequencies to transmit 0s and 1s.

After FSK came Phase Shift Keying (PSK) and Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM) during the 1950 to 1980s. Instead of encoding information on the frequency of the EM wave carriers, they are encoded onto the phase and amplitude and shown to be more efficient than FSK.

Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing (OFDM) came to the fore during the 1980s to 2000s. While it counts as a new modulation type, I sometimes think of it as simply replacing the pulse shape filtering step with FFTs in traditional PSK / QAM transmission streams. Today most high throughput communications like WiFi and Cellular uses OFDMs.

Given the ubiquity of OFDM / PSK / QAM waveforms, and the fact that I can’t think of any other physical aspect of a signal besides amplitude, phase and frequency that could be used to carry information, I implicitly thought that there was no more room for fundamental innovation in modulation design. My stagnant view of the field was however changed when I noticed a new development called Orthogonal Time Frequency Space (OTFS).

History

OTFS was first published by Cohere Technologies in a workshop paper in 2016. This novel concept of delay-doppler communications caught the attention of many in academia and industry. Subsequently, research interest in the topic grew. Variants of OTFS were studied as well as their potential applications like cellular and space communications. A major milestone for OTFS came when MATLAB’s communications toolbox included OTFS in its 2024a update

Motivation: The problem of multipath

In this section, I will motivate the need for OTFS as a means to address the shortcomings of existing PHY designs in dealing with high-mobility multipath.

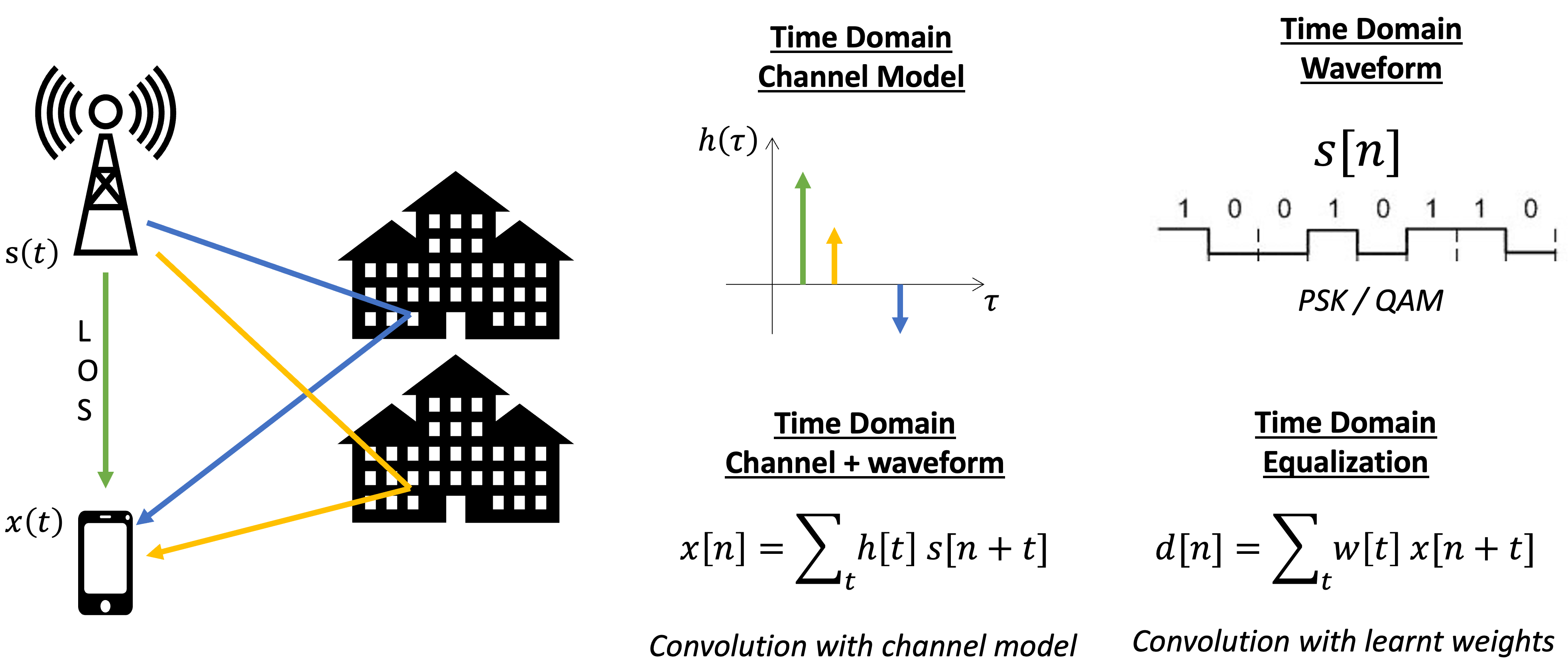

Time Domain Channel Model

Traditionally, communication models assume a wireless channel which, in addition to introducing white noise, introduces multipath between a transmitter and receiver. In the example above, the wireless channel consists of a line-of-sight (LOS) path (🟢) and delayed multipaths (🟡 and 🔵). This channel can be sparsely represented through the time-domain channel impulse response. The LOS path is represented by the dominant peak at 0 delay, and the multipaths are smaller peaks at their respective delays.

The signal is a vector of symbols in the time domain. Analytically, the expected received signal is a time domain convolution between the transmitted signal and the channel model. The receiver then approximately undo the multipath by performing another time-domain convolution between the equalizer weights and the received signals. The equalizer weights are typically learnt from the pilots in the signal. They represent the approximate inverse of the channel model and are assumed to be approximately stationary so that the learnt weights are still applicable after the pilots are transmitted.

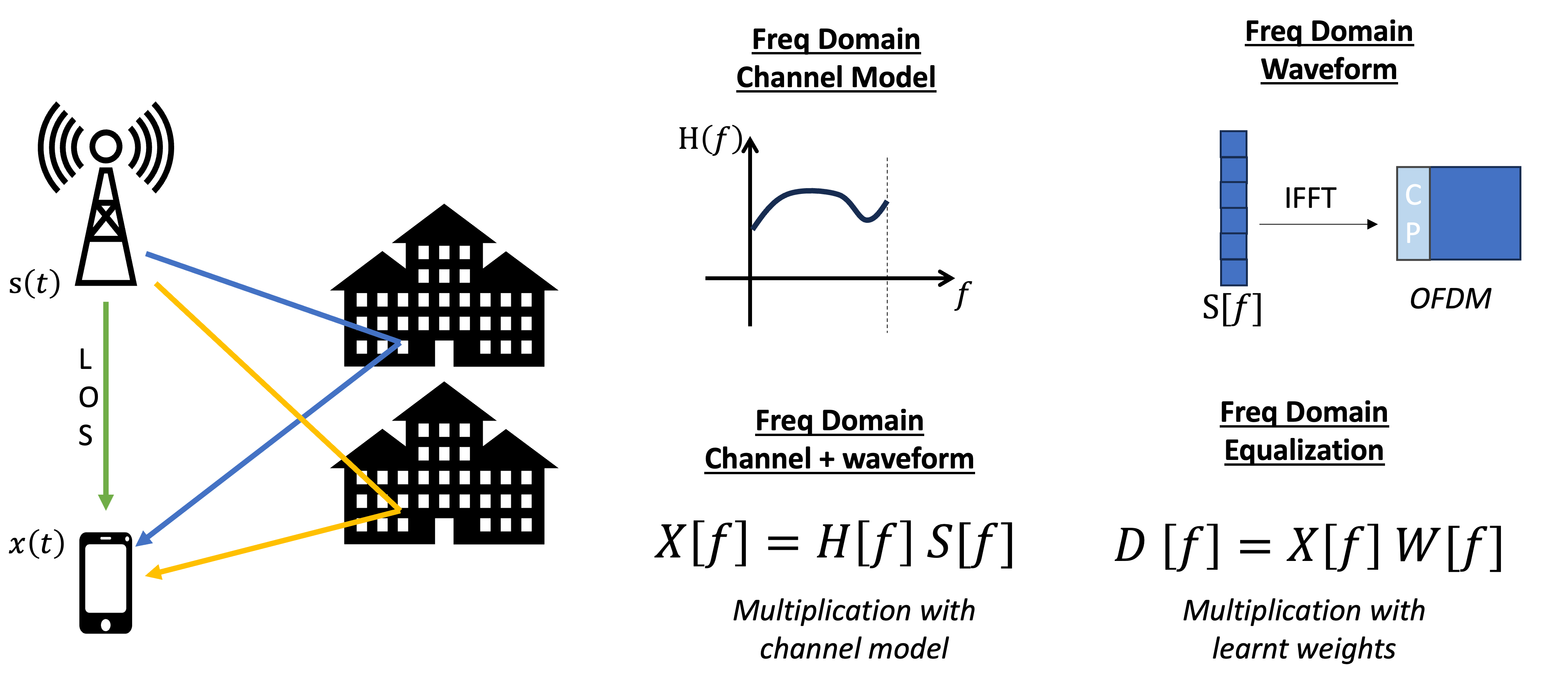

Frequency Domain Channel Model

Time domain equalizers needs to have kernel sizes that spans at least as long as the greatest multipath delay (delay spread). For example, if the greatest delay path in the channel is $T=1ms$, the equalizer weights need to be as long as $BT$ where $B$ is the baud rate of the signal. Now, as baud rate of the signal rises, so does the computational cost of equalization. A 1MHz signal would need an equalizer at least 1000 samples long to handle a 1ms delay. With more weights to learn, the equalizer would need more training samples in order to converge. Not only that, it might be numerically unstable within finite integer precision DSP chips.

OFDM provides an innovative solution to scaling communication signal bandwidth. OFDM places symbol information within the frequency domain. Each subcarrier has bandwidth small enough such that we can assume it only experiences flat fading ( channel simple scales the phase and amplitude) and can be corrected by a one-tap equalizer.

OFDM equalization is done in the frequency domain. Equalizer weights are still learnt from pilots OFDM symbols. Each learnt weight represents the inverse channel at that subcarrier frequency.

While the number of equalizer weights needed for OFDM still scales linearly with the baud rate, it is typically fewer than that needed by wideband signal carrier PSK waveforms. The single tap equalization performed on each subcarrier is also numerically simple and stable.

Problem: Doubly Spread channels

The time-domain channel model assumed a time-domain channel model, designed a time-domain waveform, and performs equalization in the time-domain.

The frequency-domain channel model (OFDM) assumed a frequency-domain channel model, designed a frequency-domain waveform and performed equalization in the frequency-domain.

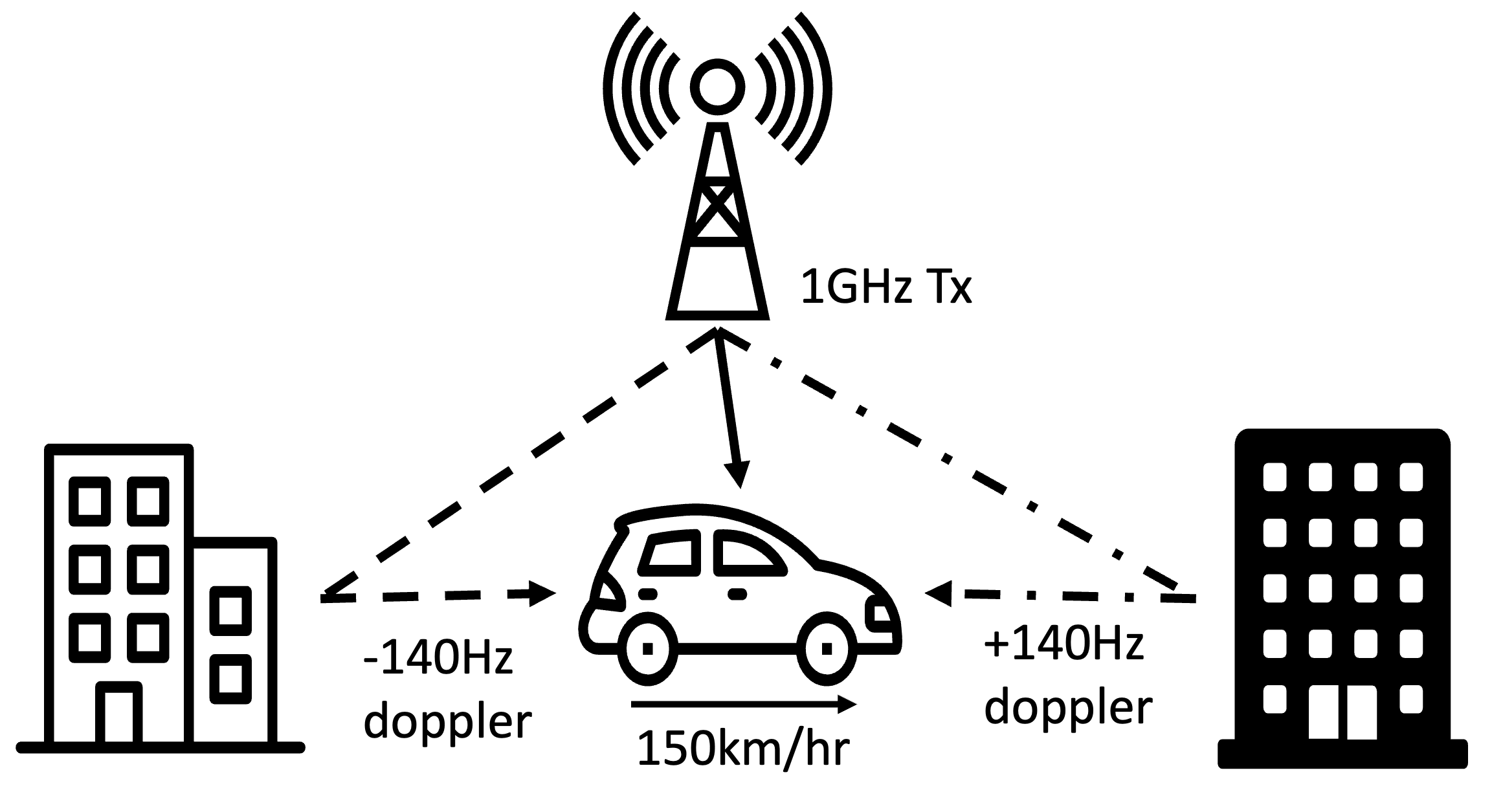

However, both channel models still assumed a static physical scenario where the multipath only has a time delay but no frequency offset (doppler). As wireless technologies use higher carrier frequencies (> 6GHz), the effect of doppler becomes more significant, especially as wireless communication are onboarded to high-mobility platforms such as high speed train or even LEO satellites.

However, both channel models still assumed a static physical scenario where the multipath only has a time delay but no frequency offset (doppler). As wireless technologies use higher carrier frequencies (> 6GHz), the effect of doppler becomes more significant, especially as wireless communication are onboarded to high-mobility platforms such as high speed train or even LEO satellites.

When there is doppler in the multipath, the time-domain (delay profile / impulse response) representation of the channel is no longer stationary. The phase shift induced on the blue and yellow multipath constantly change, breaking the assumption of channel stationarity required for equalization. It is not just the time-domain representation that isn’t stationary, the equivalent frequency domain representation of the channel assumed in OFDM also is not stationary.

Such a channel with time delay and frequency offset of multipath is called a doubly spread channel.

Solution : Delay Doppler Domain

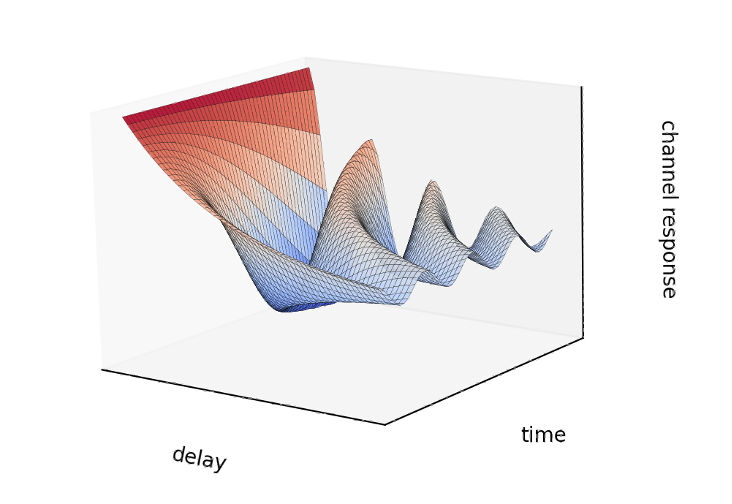

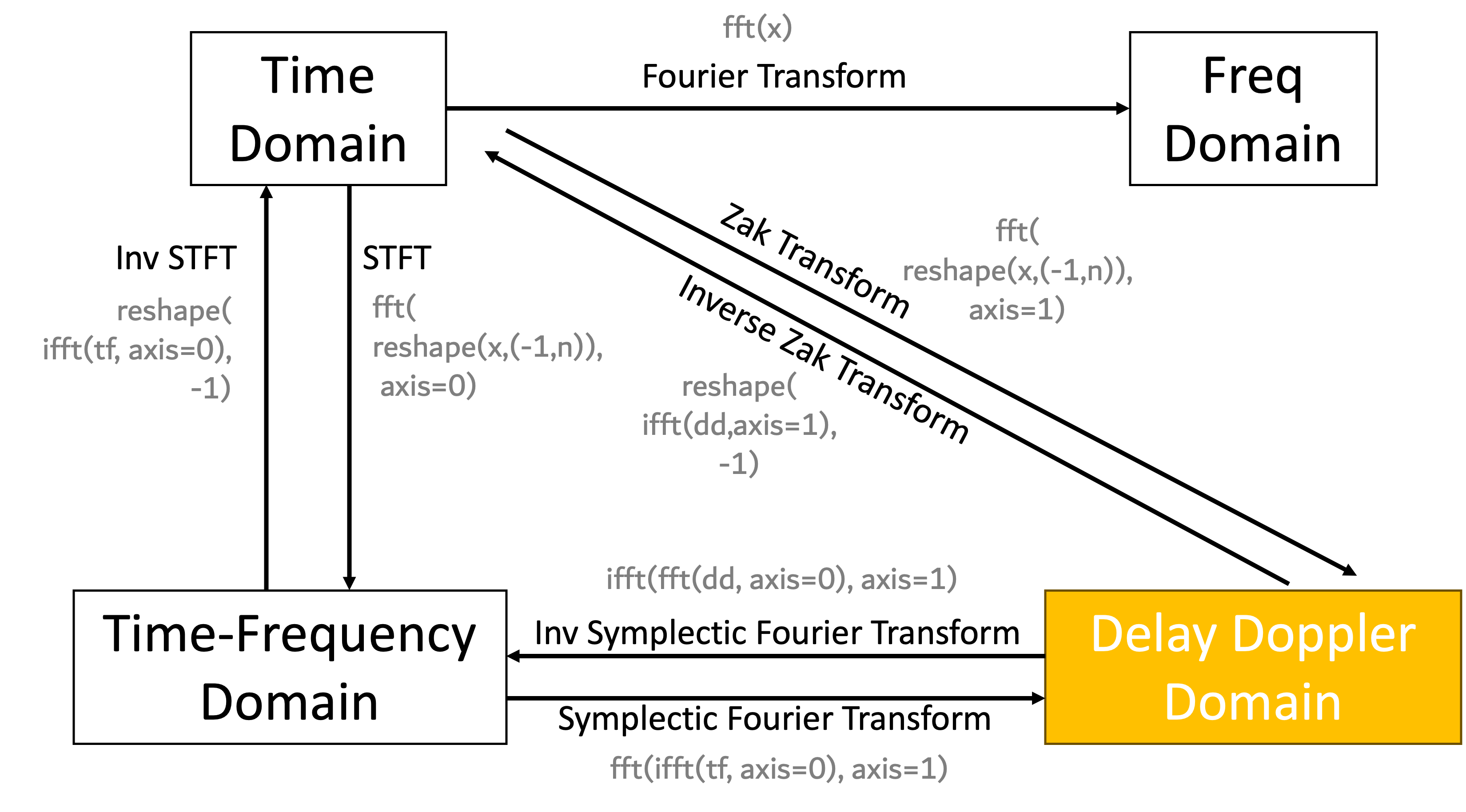

PSK / QAM modulations and equalizations were designed in the time domain. OFDM modulation and equalization were designed in the frequency (arguably also the time frequency domain). In constrast, OTFS modulation and equalization is designed in the delay doppler domain. But what is the “Delay Doppler” domain? At a high level, the delay doppler domain can be treated as simply another representation of a signal just like the frequency domain. While the fourier transform maps a time-domain representation of a signal into the frequency domain, the Zak Transform maps the time-domain representation of a signal into the delay-doppler domain. The figure above shows the relationship between the domains.

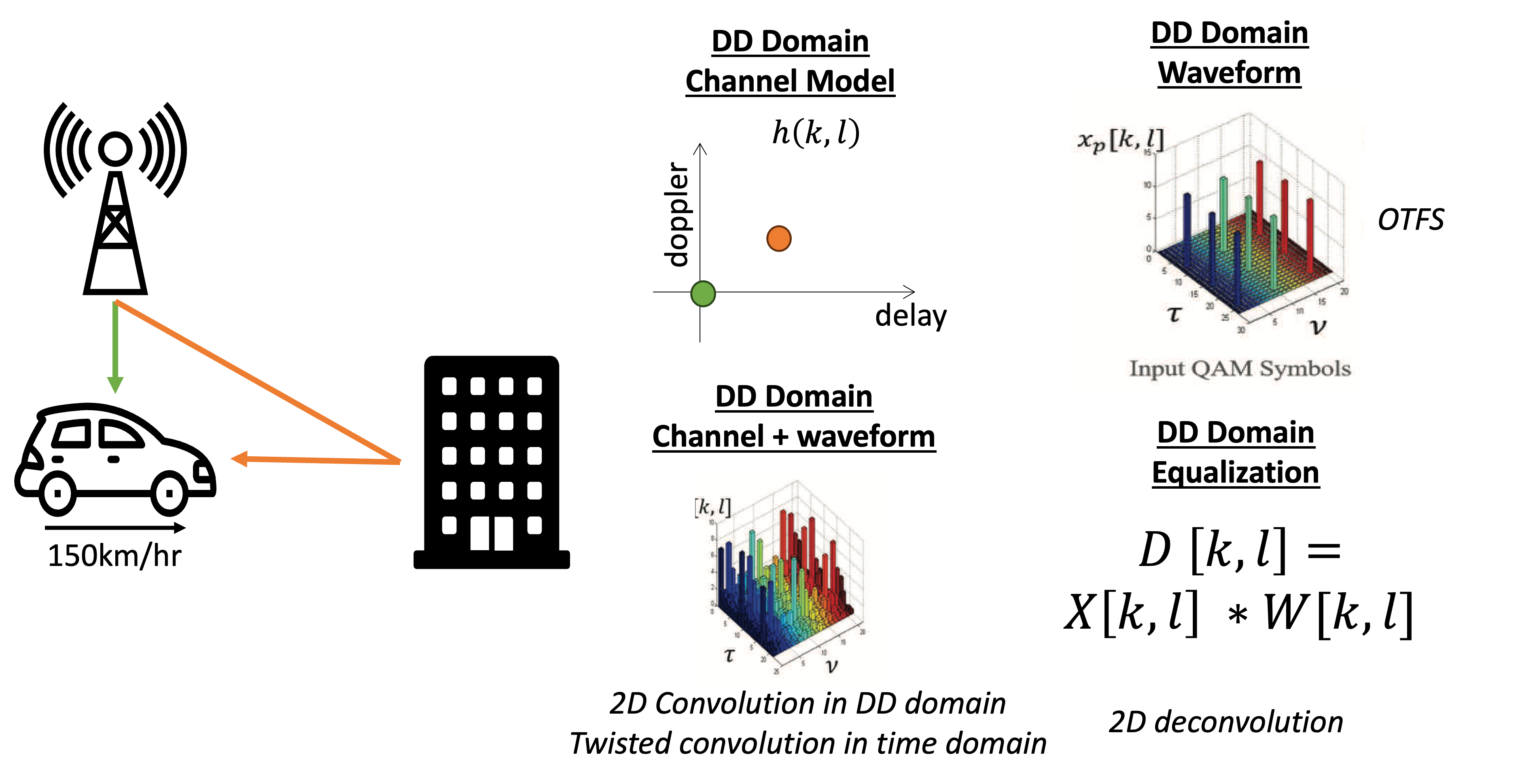

A major benefit of the delay doppler domain is the ease of representating a channel with a multipath that comprises time delay and frequency offset. Unlike traditional time-domain or frequency domain representation of the channel, the delay doppler representation of a doubly spread channel is stationary. When transmit symbols are encoded in the delay doppler domain, the received symbols are simply a 2D convolution in the delay doppler domain between the transmit symbols and the channel representation. Equalization in the delay doppler domain could then be easily compensate for the effect of the channel.

Discussion

I see OTFS as an elegant solution to the problem of doubly spread channels. There is an alternative track of research seeking to use AI / neural networks to replace the traditional equalizer in traditional comms. For doubly spread channels, a two or three layer neural network could in principle outperform traditional equalizers which are nothing more than a single layer CNN. But it comes at a cost of increased compute and thus energy usage. If OTFS can effectively equalize the signal for all doppler regimes, I think it should be the way to go for 6G.

Resources

Books

- 2021, OTFS: A waveform for 6G

- 2023, Delay-Doppler Communications: Principles and Applications

- 2024, OTFS Modulation: Theory and Applications

Youtube Videos

- 2023, What is OTFS? Orthogonal Time Frequency Space Modulation (“Best video in youtube for OTFS”)

- 2024, Exploring OTFS Modulation in 6G and Beyond: Easy Explained with Python & MATLAB Code

- 2025, Delay Doppler, Zak-OTFS, and Pulse Shaping Explained

Papers

Introductions, Fundamentals and Surveys

- 2017, Orthogonal Time Frequency Space Modulation

- 2019, Sparsity in the Delay-Doppler Domain for Measured 60 GHz Vehicle-to-Infrastructure Communication Channels

- 2021, Orthogonal Time-Frequency Space Modulation: A Promising Next-Generation Waveform

- 2021, Derivation of OTFS Modulation From First Principles

- 2021, Performance Analysis of Coded OTFS Systems Over High-Mobility Channels

- 2021, Performance Analysis of OTFS Under In-Phase and Quadrature Imbalance at Transmitter

- 2022, An Overview of OTFS for Internet of Things: Concepts, Benefits, and Challenges

- 2022, Orthogonal Time Frequency Space Modulation—Part I: Fundamentals and Challenges Ahead

- 2022, Orthogonal Time Frequency Space Modulation—Part II: Transceiver Designs

- 2022, OTFS vs. OFDM in the Presence of Sparsity: A Fair Comparison

- 2023, Orthogonal Time Frequency Space Modulation—Part III: ISAC and Potential Applications

- 2024, A Survey on Orthogonal Time Frequency Space Modulation

- 2025, A Unifying View of OTFS and Its Many Variants

Waveform Design: Detection, Channel Estimation, Equalization

- 2018, Interference Cancellation and Iterative Detection for Orthogonal Time Frequency Space Modulation

- 2019, Channel Estimation for Orthogonal Time Frequency Space (OTFS) Massive MIMO

- 2019, Practical Pulse-Shaping Waveforms for Reduced-Cyclic-Prefix OTFS

- 2020, A Simple Variational Bayes Detector for Orthogonal Time Frequency Space (OTFS) Modulation

- 2021, Message Passing-Based Structured Sparse Signal Recovery for Estimation of OTFS Channels With Fractional Doppler Shifts

- 2021, A Robust Baseband Transceiver Design for Doubly-Dispersive Channels

- 2021, Low Complexity Precoding and Detection in Multi-User Massive MIMO OTFS Downlink

- 2022, Cross Domain Iterative Detection for Orthogonal Time Frequency Space Modulation

- 2022, Learning to Equalize OTFS

- 2022, OTFS Channel Estimation and Data Detection Designs With Superimposed Pilots

Multiple Access

- 2019, OTFS-NOMA: An Efficient Approach for Exploiting Heterogenous User Mobility Profiles

- 2019, OTFS-Based Multiple-Access in High Doppler and Delay Spread Wireless Channels

- 2021, A New Path Division Multiple Access for the Massive MIMO-OTFS Networks

- 2022, Low-Complexity ZF/MMSE MIMO-OTFS Receivers for High-Speed Vehicular Communication

Implementations and Applications (Sensing, etc)

- 2019, OTFS Modem SDR Implementation and Experimental Study of Receiver Impairment Effects

- 2020, On the Effectiveness of OTFS for Joint Radar Parameter Estimation and Communication

- 2020, Performance Evaluation of OTFS over Measured V2V Channels at 60 GHz

- 2021, Integrated Sensing and Communication-assisted Orthogonal Time Frequency Space Transmission for Vehicular Networks

- 2022, OTFS-based Joint Communication and Sensing for Future Industrial IoT

- 2022, A Novel ISAC Transmission Framework based on Spatially-spread Orthogonal Time Frequency Space Modulation,

- 2022, OTFS-TSMA for Massive Internet of Things in High-Speed Railway